Section 65B of Indian Evidence Act has been perhaps the most difficult techno legal concept that was introduced by ITA 2000 (Information Technology Act 2000) which even after 20 years of its existence, is yet to be uniformly understood.

The reason why it is difficult for advocates and judges to quickly grasp the intricacies of Section 65B is that they keep looking at the section with a wrong perspective of “Secondary Electronic Evidence” and compare it with the secondary documentary evidence discussed in sections immediately before and after Sections 65A and 65B.

In order to understand Section 65A and 65B, we need to close our eyes to sections 62,63,64, 65 and 66 of Indian Evidence Act. Instead we need to keep in our mind, Sections 3, 17, 22A. Additionally we need to understand the way Computers represent data and data storage which we call as “Evidence” and try to extract in a manner which human beings can understand.

These sections regarding admissibility of electronic evidence came into the statute on 17th October 2000. It was used in 2004 in the AMM Court Egmore resulting in the historic conviction of Suhas Katti, which was the first case in which conviction was obtained under ITA 2000. However in many other cases Section 65B was referred to but was never seriously taken note of either by the Court or the advocates. In the Afzal Guru case in 2005, Supreme Court ignored the need for mandatory requirement of Section 65B certificate and it became a precedence until in 2014, in the PV Anvar Vs P K Basheer, the Supreme Court (3 member bench) categorically expressed that Section 65B Certificate was mandatory for admissibility of Electronic evidence. This judgement also distinguished between “Admissibility” and “Genuinity” and stated that at the Admissibility stage, Section 65B is mandatory. However, the genuinity of an admitted evidence could be questioned subsequently during the trial.

In 2018, while deciding on an SLP the Shafhi Mohammed Vs State of Himachal Pradesh, a two member bench of the Supreme Court over ruled the earlier 3 member judgement and stated that

a) Where the device in which the original electronic document is present is in the custody of the person presenting the evidence, Section 65B certificate is required

b) Where the device in which the original electronic document is present is not in the custody of the person presenting the evidence, Section 65B certificate is not required.

Shafhi Mohammad Judgement is Totally Illogical

This decision was completely illogical since in the case where the device holding the electronic document is present, the presenter can as well bring it directly as an “Evidence Object” and let the Court appreciate the individual evidence contained there in in any manner it deems fit with or without certificate.

On the other hand, if a person claims that the device in which the electronic evidence is present (or was present and might have been deleted now) , is not in his posession, then he need not produce any Section 65B certificate and simply present a print out (or a CD etc) and claim that it has to be admitted as evidence.

As a result accepting this argument is a direct invitation for admitting manipulated electronic evidence in the hearing.

In fact the need for Section 65B Certificate is greater when the device containing the electronic document cannot be brought directly into the Court.

Primary Vs Secondary argument

In the case of an electronic document, it is better to avoid a distinction of “Primary” and “Secondary” documents and not look for sections in the Indian Evidence Act applicable for “Primary Electronic Evidence” and “Secondary Electronic Evidence”.

If we look at Section 17 of IEA (Indian Evidence Act), it states:

An admission is a statement, 1[oral or documentary or contained in electronic form], which suggests any inference as to any fact in issue or relevant fact, and which is made by any of the persons, and under the circumstances, hereinafter mentioned.

Note that this section refers to a statement in three forms namely Oral, Documentary and Contained in Electronic Form.

The legislative intent in this section is to consider an “Electronic Document” as neither “Oral” nor “Documentary” but as a third category of statement different from the other two.

Section 22A and Section 59 speak of “Oral Evidence as to the contents of an Electronic document”.

Section 22A states that

Oral admissions as to the contents of electronic records are not relevant, unless the genuineness of the electronic record produced is in question.]

Section 59 states that

All facts, except the 1[contents of documents or electronic records], may be proved by oral evidence.

These two sections address the elimination of whether an electronic document can be proved by oral evidence or not and clearly states it cannot be proved by oral evidence.

Then IEA discusses under Sections 61,62,63,64 65 and thereafter in 66, different aspects of documentry evidence discussing how proof of contents of documents are to be produced.

Section 61 introduces the concept of Primary and Secondary Evidence. Section 62 refers to “Primary Documents” being presented in the Court. and Section 63 refers to what is a secondary document. Sections 64 and 65 indicate instances when Secondary evidence may be used instead of the Primary evidence.

After thus exhausting the discussion on Oral and Documentary evidence, IEA addresses Electronic Evidence which is the third category of evidence referred to in Section 22A. Section 65A states clearly that this is a “Special Provision” and goes on to state that

The contents of electronic records may be proved in accordance with the provisions of section 65B.

After thus introducing the special nature of the Section 65B, the Act goes on to explain how “Admissibility” of electronic evidence is provided.

We must note that in respect of electronic documents, what is presented when a hard disk or a CD is produced is not the “Primary Document” but a container of electronic documents of which a part is the evidence document. Also, the secondary documents indicated in Section 63 refer to copies made by mechanical process, copies made by comparison with the original etc. These donot apply to the Electronic Documents.

Hence what is applicable to electronic documents and how it may be produced for admissibility is entirely covered only under Section 65B and nothing else.

If we look at Section 65B, it contains 5 sub clauses of which the very first sub clause “Section 65B(1) sets the stage for the other 4 sub clauses.

Section 65B(1) clearly starts with the statement “Notwithstanding anything contained in this Act” and hence once again confirms that the earlier sections 62 to 65 are not to be brought in in the interpretation of this section.

Section 65(B) also indicates that the electronic evidence can be produced for admissibility in two forms, either as a Print form or as a copy in a media.. Both these forms of presentation of information are referred to as “Computer Output” for further sub sections.

Section 65B(1) then states that such a Computer Output shall be deemed to be also a document and shall be admissible as evidence without further proof or production of the original, if conditions mentioned further are satisfied.

Section 65B(2) then continues and states that the conditions referred to in sub section (1) in respect of the computer output shall be ….

Note the use of the words “In respect of the computer output” in Section 65B(2). This confirms that the conditions discussed under subsections (a),(b),(c) and (d) of 65B(2) refer to the “Computer output” which is the print out or the soft copy of the evidence.

Some experts are unable to appreciate that these conditions of Section 65B(2) donot refer to the so called “Original” but to the Computer Output which is also a document. These sub clauses (a), (b) (c) and (d) and all these 4 conditions should be satisfied and all of them refer to the generation of the “Computer Output” and not the “original”.

Sub section (3) is to confirm that the provisions of Section 65B(2) will stand even when the production of the computer output is not done by a single computer but by a network of computers.

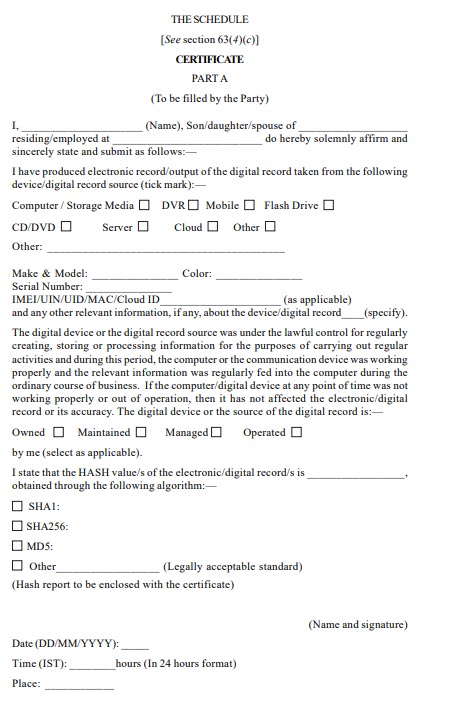

Sub section (4) lists the contents of the Certificate to be issued. It essentially expects that the electronic document which is the subject evidence is identified, the manner of its generation explained along with the devices used. The Certificate has to be signed by the person who produced the computer output. The word “responsible official position” is with reference to a device belonging to a company and it should be considered as refering to the sole owner of a computer if he is an individual.

Section 65B(4) states that the Certificate is adequate if it is stated as “To the best of the knowledge and belief” of the person signing. This limitation is not a dilution of the certificate but an acknowledgement that “What a person can certify as having seen” has certain uncertainties that are inherent to the technology and stating anything as “An absolute Truth” is not feasible. The inclusion of this limitation shows that the drafting has been done in a practically acceptable manner and not just for the theoretical satisfaction of lawyers who want to attack the evidence on one ground or the other.

Subsection 65B(5) adds certain contingent events that may arise due to the technical reasons such as use of an input from a computer or other automated devices (Perhaps it would even cover input through AI algorithms), information that may incidentally become available etc.

Overall, Section 65B has been very intelligently constructed and there is a meaning to every subsection used in the Section. This has been well recognized in the P V Anvar Vs P K Basheer judgement which came to the right conclusion that the certificate is mandatory.

Why Certification has to be mandatory

There is another technical reason why a Court cannot accept any electronic document as evidence without a human being taking responsibility to confirm even if the so called original is in the hands of a judge.

Understanding this requires a journey into the technical world of how data is stored in a computing device and how it is interpreted.

We know that all computer documents are recorded and stored in the form of a sequence of Zeros and Ones.. These Zeros and Ones reside in side the media such as the hard disk or CD either in the form of “Charge” or “No Charge” or “Pits” and “Lands” (Pits and lands refer to the way data is represented in a CD) etc. If in a portion of the hard disk there is charge, we call it as a representation as “One”. If not we call it as “Zero”. A sequence of 8 such zones constitute a byte and several bytes in a sequence form a meaningful letter or number. Whether a sequence is a number or a letter has to be determined in the context.

The “Evidence” therefore in its original form is in the form of “Charge” or “No Charge” or “Pits” and “Lands”. No human being can see a hard disk or a CD and read the data by looking at the platters or the CD surface.

The “Original Evidence” is therefore always in the form of humanly unreadable data elements. It can only be made “readable” by a human when the data is read by another device such as a hard drive or CD drive connected to a computer which picks up the data and processes it through a software application which itself rides on a hardware. Then the interpretation based on the configuration of the computer appears on the screen as readable text.

Similar processing has to be done to the sequence of binary data to render them as a sound through the speakers or image or video.

Hence in rendering any binary sequence into a human experienceable form of text, audio or video there are many software and hardware computer elements which are used. If any of these function in an inconsistent manner the binary sequence may show up differently. So the same data seen by different persons in different computers, different operating systems, different applications may appear differently.

What Section 65B does is that it designates a person who is reliable to the Court as a witness to observe the binary in a standard device and let the Court know what he saw. In order to ensure that any different observations are reconciled, the certifier who provides the certificate will record the process and the devices used so that any other person using the same type of devices would come to a similar conclusion. If he has used some strange methods and rendered the evidence, then the Court can question him why he used a non standard method and come to a conclusion whether the method used for rendering the evidence was correct or not. For this purpose the Court may use a Section 79A accredited digital evidence examiner or let the other party to counter with another expert.

Even when the Court has on hand what people normally refer to as the “Original Evidence”, what the Judge has is the CD or the hard disk or say a pen drive. If he looks at it from outside, no evidence is visible. If the Judge wants to view the document than he has to use a computer, with the right software and hardware an view it. What he views would be conditional to what devices he uses and what configuration he uses. If he has a black and white monitor and views a colour picture, he may not see what he should see. If he views a Microsoft Word document in a PDF viewer or even a Note pad, he would not see any document. If he opens a .mp4 file in a audio software, he will not see any picture. If therefore he has used certain method to view the document, then the judge himself becomes a self certifying Section 65B observer.

Since it is not proper for the Judge to be a witness himself, even in the case of the original electronic document container being in his hands, the Judge should rely on a trusted third party to provide the Section 65B evidence and not view and record the electronic evidence himself.

This delicate issue was recognized by the magistrate who was adjudging the Trisha Defamation case in the Chennai Egmore AMM court some time in 2004. No other court till date has recognized this aspect.

Looking at all the points made above, Section 65B has been well drafted and mandatory certification is unavoidable.

I therefore urge advocates and experts who are trying to support the faulty Shafhi Mohammad judgement to realize that they are not correct in their view point and should not mislead the bench which is hearing the reference in the case of Arjun Panditrao Khotkar V. Kailash Kushanrao Gorantyal.

I wish any of the readers of this article forward a copy of this article to the honourable bench of the Supreme Court which is now hearing/or has heard the reference related arguments presented by otherwise eminent advocates.

Naavi